With anthelmintic (dewormer) resistance becoming worse every day, equine parasitologists are helping horse owners change to sustainable worm control management practices to protect and keep horses safe as long as possible from resistant worms.The ex-racehorse or other kind of horse that you bring home may come from a property where resistance levels are high due to overuse of anthelmintic (dewormer) drugs.

For the most part horse worms come from other horses and the ground. The biggest thing is that they come from other horses.

Once you introduce resistant horse worms onto your property, there`s no going back, they stay, breed, and make more resistant worms until all horses carry a load of resistant worms that can`t be killed by dewormers.

The Australian Society for Parasitology states it well: "Once you have it – it`s too late."

Thanks to Dr Anne Beasley we have permission to share her important article just written for the Queensland Racing Integrity Commission (QRIC) with you. It is specifically targeted at potential Off The Track (OTT) horse owners, but all the principles are true for any horse. Please keep reading to find out ways to improve the sustainability of your worm control management on your property.

You can read the full article on the QRIC webpage ( coming soon)

Sustainable worm control for horses

Managing worms in an off-the-track horse is no different to managing worms in any other kind of horse, after all, a horse is a horse (as far as worms are concerned)! There are, however, some key points worth making in relation to bringing your OTT horse home to your property. History repeating… It has been commonplace for many decades to de-worm horses frequently from a very young age. This was, in fact, the advice put forward by experts of that time (1960’s) to prevent the build-up of harmful infections of Strongylus vulgaris, the most dangerous of all horse worms. Understandably, horse owners and breeders (particularly those with large numbers of valuable horses) want to prevent any ill-health arising from parasite infections, and so undertake a regular de-worming schedule whereby all horses are treated for worms approximately every 6-8 weeks. This aggressive approach to worm control definitely served its purpose in the past – so much so that Strongylus vulgaris is a rare find these days. Unfortunately, an unintended consequence of frequent de-worming has emerged to complicate matters. Rise of resistance. Although Strongylus vulgaris has not been able to stand up to our constant chemical barrage, other equine worms, including the small strongyles and Parascaris equorum (the large roundworm of foals) have emerged victorious by developing resistance to most of our available anthelmintic drug classes. Knowing this, and understanding how it came about is one of the most valuable investments you can make in your own education with regards to setting up sustainable worm control practices on your property. In addition, getting to know the difference between drug ‘classes’ and ‘active ingredients’ is essential for selecting the right product/s to use. There are really only three broad-spectrum drug ‘classes’ available to choose from; the benzimidazoles (or ‘BZ’s’), the tetrahydropyrimidines (or ‘THP’s’) and the macrocyclic lactones (or ‘ML’s’ / ‘mectins’). There are multiple active ingredients that belong to each of these drug classes but each of these works in the same way to kill the worms. Think of the drug class as a ‘family’ and the active ingredients as ‘siblings’.

Quarantine

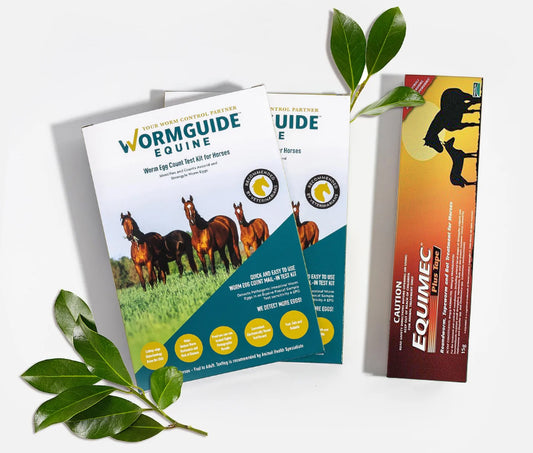

The ex-racehorse that you bring home may come from a property where resistance levels are high due to overuse of anthelmintic drugs. Many studies have shown that a significant proportion of horse owners still use an interval style treatment regimen with intervals of 8 weeks or less. You should adopt strict biosecurity practices so that you don’t import a resistance problem onto your own property. A good quarantine strategy involves removing the existing worm burden of your new horse before allowing him/her to move onto your main pastures. To ensure you do a thorough job of this, it is advised that you treat the horse with each of the available broad-spectrum drug classes. One suggestion would be to use a combination product containing a BZ + THP (e.g. Strategy-T or Kelato Revolve) in addition to a product containing an ML and praziquantel (e.g. Equest Plus). I have suggested Equest Plus for this because it contains the active ingredient Moxidectin, which has good efficacy against larvae that are encysted in the wall of the horse’s large bowel (the other ML’s do not). After you have administered these products to your new horse, keep him/her separate for the next 10-14 days (a dirt yard is ideal for this quarantine period). You can then check that your anthelmintic treatment has been effective by collecting a fresh manure sample and having a faecal egg count (FEC) performed by your local vet or service provider.

Modern worm control

Once your new addition has transitioned onto your property, you should develop a worm management plan that is sustainable. Let’s be honest, a calendar-based de-worming regimen for all horses is a very convenient approach to worm control – but continuing this practice will only serve to increase resistance levels to the point where anthelmintic drugs become practically useless. Modern worm control practices instead rely on incorporation of non-chemical strategies, which ultimately help to reduce the reliance on chemical dewormers (thereby reducing the development of resistance). The practicality of these nonchemical strategies will depend on the size of your property, the number and age of the horses you have, and of course, your own level of commitment to change. As such, there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach – you’ll need to pick and choose the elements that are appropriate for your property. Here are some possible strategies for you to consider.

Monitor

Always try to make decisions based on actual evidence. Don’t guess, measure! One way to get to know the worm egg-shedding patterns of your new horse (and others you may have) is to monitor their FEC. Do this 3-4 times over a year and you’ll develop a good feel for whether your horse is a chronic high-shedder, a low-shedder, or somewhere in between. Research has shown that adult horses tend to have fairly consistent egg-shedding patterns – so a high shedder is usually always a high-shedder. The best time to collect a sample for a FEC is just prior to de-worming, provided the horse has not been de-wormed in the previous 10 weeks or so (You won’t learn much about your horse’s egg-shedding patterns while the previous anthelmintic is still having an effect!). Younger horses, with developing immune systems, typically shed higher numbers of eggs and will therefore require more frequent treatment. For this reason, monitoring of FEC’s is a practice that is most useful for mature horses.

Keep it clean

Removal of manure from pastures is probably the most effective way of interrupting the parasite life cycle. This might be a practical solution for you if you keep your horse/s on small acreage, but not at all practical if you have large paddocks. During the warmer months of the year in QLD (mid-autumn through to late spring), worm eggs hatch rapidly and so manure should be removed every second day to be effective. This can be relaxed slightly during the cooler winter months to twice per week.

Rest it!

Fortunately, the infective larvae (L3’s) of small strongyles don’t live forever on pasture. They will die off over time, especially if the environmental conditions are unfavourable. Hot, dry weather is particularly detrimental for their survival, and so spelling pastures over the hottest part of summer (for a couple of weeks when temperatures are in the high 30°C’s) is a great way to reduce pasture infectivity. During spring, autumn and winter (in south-east QLD), however, infective larvae will survive for much longer, and so spelling pastures becomes far less effective. You would need to spell pastures for several weeks to months to have the same kind of effect which is often not practical. If you have foals and young horses (< 2yo) on your property, they may be shedding eggs of the large roundworm (Parascaris equorum). These eggs are very tough and do not hatch in the environment like those of the small strongyles. In fact, they can remain viable on the pasture for up to 5 years! So pasture spelling is not an effective control strategy for this parasite – manure removal, if possible, would be far more effective.

Spread it!

Spreading manure is a popular practice on horse properties. The same principles for pasture spelling apply to this practice – spreading will be far more effective for small strongyle control if undertaken during hot dry weather. Breaking up the faecal balls to expose worm eggs and larvae to high temperatures (high 30°C’s) over a week or more will lower the infectivity of the pasture significantly. If you spread manure during the cooler months, however, you are essentially spreading infective larvae across your pasture, which will survive quite well and ultimately increase transmission to all horses grazing that pasture.

Mix it up!

Because parasites are, for the most part, host-specific (i.e. horse parasites live only in horses, and cow parasites only in cows), you can make use of cross-grazing with livestock. If you happen to have cattle or sheep on your property, you can rotate them through your horse pastures and they will essentially ‘vacuum’ up the horse worm larvae without becoming infected themselves. Very recently, some French researchers validated this strategy and showed that young horses grazed with cattle had 50% fewer strongyle eggs excreted in their faeces than horses grazed in equine-only pastures.

Conclusion

Parasites, their lifecycles and their survival in the environment are complex topics, but you don’t need to be an expert to master a few key strategies and improve the sustainability of your worm control plan. Adopting some of the strategies above that align with your current farm management practices will not only reduce your dependence on chemical de-wormers and delay the onset of anthelmintic resistance, it may also save you money in the long run.